︎︎︎

After the Happy Ending

Portrait of Julie

Legouez

by Josefin Granetoft

One often comes to an appreciation of love first through its absence, in abandoned promises, in ghostly messages lingering on screens, or during lonely nights of longing for the blissful, ecstatic thing we call love. Much like how cliché-ridden pop songs are cherished as guilty pleasures, it seems that love itself induces a mixed feeling of delight and embarrassment. Most of us want to love and be loved. But it can be uncomfortable to admit that one’s personal happiness is reliant on others. To want love, especially in the form of traditional monogamy, seems hopelessly outdated, needy, if not a tad obscene.

The Berlin-based artist Julie Legouez does not shy away from the obscenity of love. She proclaims our longing for emotional attachment, while exposing the contradictions of romantic ideals. Her work often takes the form of personal revelation, drawing on material from her private life as a primary medium. When I visited Legouez in her former studio last year, she talked to me about her personal life and her artistic process with equal openness. By using her own romantic life as a reference, she seeks to investigate love in all its versions: unidealized, unsuccessful, and unrequited. She balances sincerity with irony and humour, often appropriating pop cultural imagery and tropes, by which she highlights the close link between intimate relationships and social structures.

Her process almost always starts with writing, a practice that has accompanied her from a young age. She attempted to draft her first novel when she was thirteen and has kept a personal diary ever since. In her early work, she often transferred phrases from her personal notes and diaries into painting, which was her chosen medium in art school. But with time she started to question her own method. Instead of treating her personal notes as references for painting, she decided to display them just as they were. For example, one of her student projects was an exhibition of personal secrets that she had scribbled onto a plain paper.

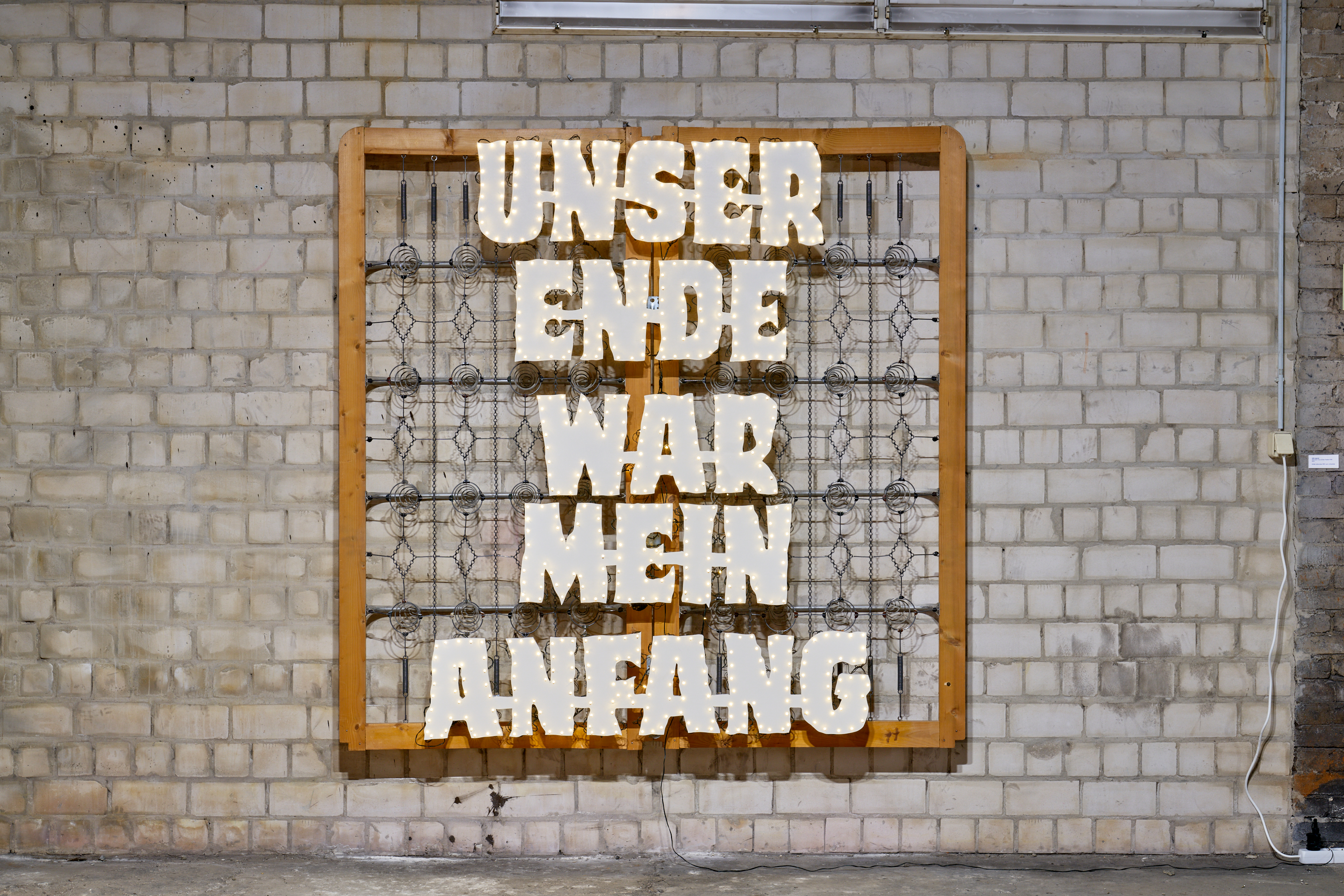

Zitat einer Frau auf dem Friedhof 1995, 2022. Exhibition view: Dear Diary, Culterim Gallery, Berlin, 2022. Photo: Marlene Burz.

Depression (Have you tried jogging?), 2022. Exhibition view: Dear Diary, Culterim Gallery, Berlin, 2022. Photo: Marlene Burz.

Legouez today describes herself as a confessional artist, naming Tracey Emin and Sophie Calle as important inspirations. Similar to these artists, Legouez documents and narrativizes events of her private life as part of her practice. Her work comprises multi-media installations, paintings, and videos, oftentimes integrating documents, photographs, and other objects as ready-mades from her own life. Confessional art can be seen as a reflection of a general tendency to share and consume intimate narratives, evidenced by social media behaviour and reality TV.1 Legouez notes that her best works are often the ones that she finds the most embarrassing or uncomfortable to show. But she does not simply seek to create a spectacle out of herself. Instead, she encourages the viewer to identify and mirror themselves in her experiences, which include lovesickness, depression, and abuse.

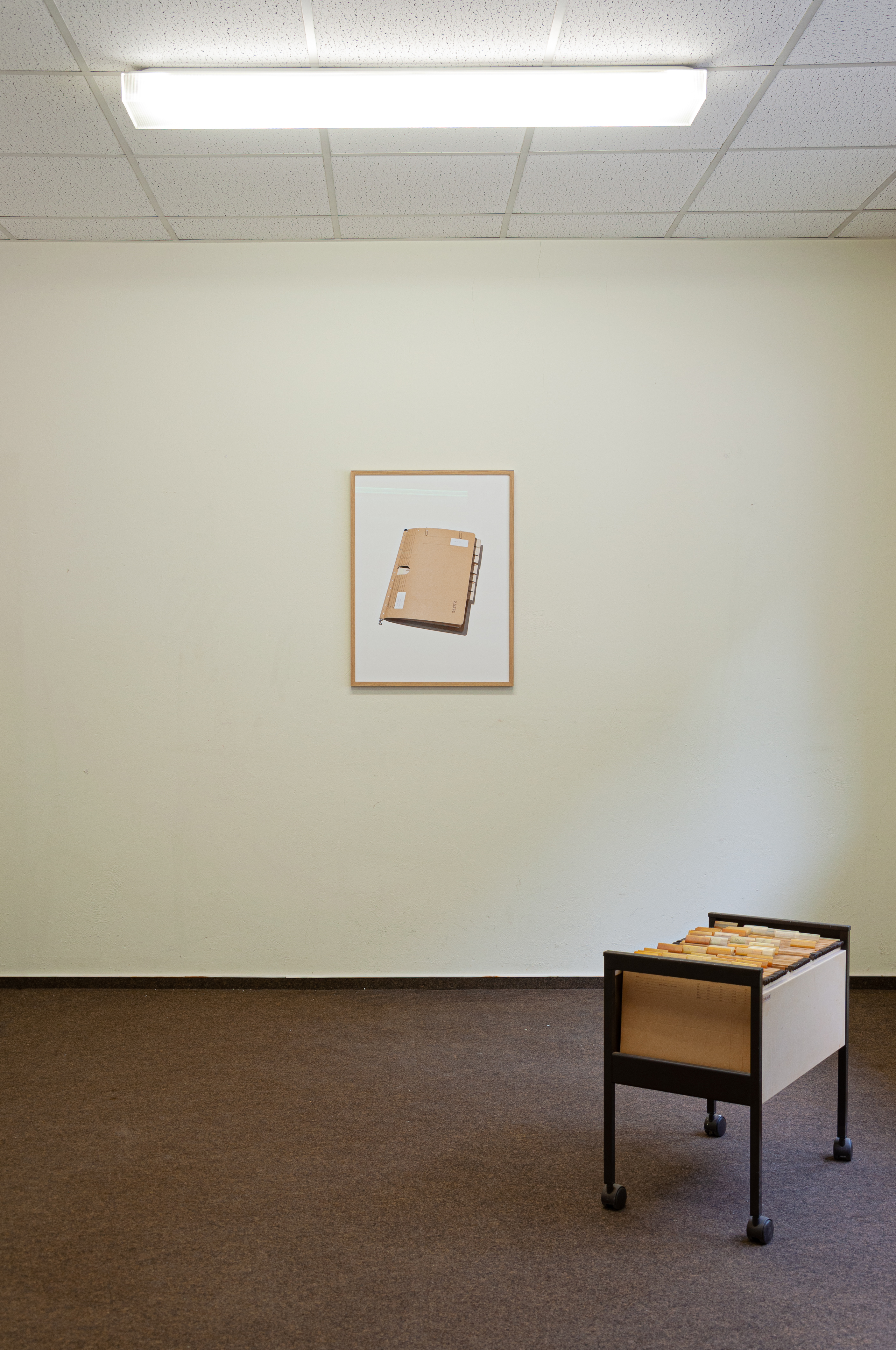

In one of Legouez’s latest works, Aktenzeichen 512-261 AW//JL 22… (2022), she lets the viewer in on a recent breakup. The separation itself is treated like a crime scene, the installation its investigation. Illuminated by an overhead fluorescent light, a bleak scene meets the viewer: an anonymous wall clock, a filing cabinet, a desk cluttered with office supplies. Central to the installation is a photograph of an archival file containing diary pages, poems, and photographs of objects with emotional value, which Legouez collected after the breakup. She documented and assembled all the objects into a single file, which was then sent to her ex-lover, who was asked to confirm the arrival of the parcel in writing.

Aktenzeichen 512-261 AW//JL 22 (Denn du bist verrückt genug, um dich in dieser Welt zu verlieben. Aber die Welt ist viel verrückter als du und fast wär etwas von uns geblieben.), 2022. Installation view: Übern Berg, Localize Festival, Potsdam. Photo: Julie Legouez.

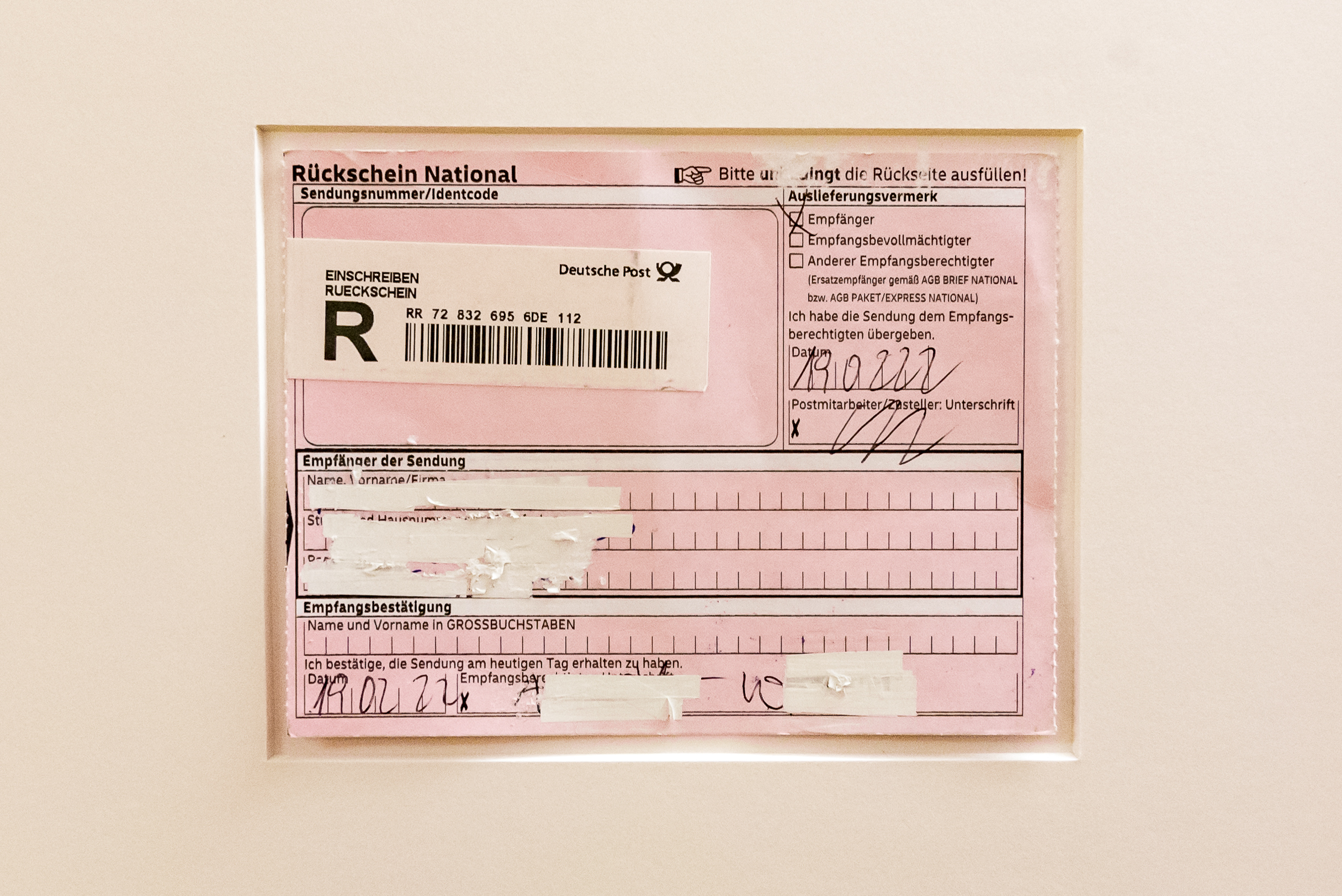

What remains, except for the documentation, is merely the return receipt: a cold, transactional object. Expressed in the language of administration, it is a perfect metaphor for the business-like logic of modern-day romance. Love is not just governed by feelings, but all the more by self-interest and a sense of investment. Legouez’s appropriation of administrative tools effectively nullifies the emotional value of the personal items. She logs and files the objects away, stripping them of their sentiments. A broken heart becomes a matter of classification. Most striking is the physical absence of the file itself, an absence that echoes the lack of emotions embedded in the work’s bureaucratic language.

Aktenzeichen 512-261 AW//JL 22 (Denn du bist verrückt genug, um dich in dieser Welt zu verlieben. Aber die Welt ist viel verrückter als du und fast wär etwas von uns geblieben.), 2022. Installation view: Übern Berg, Localize Festival, Potsdam. Photo: Julie Legouez.

Aktenzeichen 512-261 AW//JL 22 (Denn du bist verrückt genug, um dich in dieser Welt zu verlieben.

Aber die Welt ist viel verrückter als du und fast wär etwas von uns geblieben.), 2022. Detail view. Photo: Julie Legouez.

In other works, the personal testimony of the artist stands out for how strongly it affects the viewer. The series Hope is Not Enough (2020), which consists of photographs and diary entries, documents Legouez’s experience of domestic violence. The images stem from the forensic medical report she commissioned after being physically assaulted by a former partner. We see the artist’s exposed gaze and her bruised skin facing the camera. The clinical value of these photographs cannot remove the emotional force of the story they are telling. I asked Legouez about her choice to make this experience public. She admitted to having doubts about it, considering the potentially negative reactions of the implicated person, her friends, and family. But in the end, precisely the prevailing stigma and lack of awareness of sexual violence made it important for her to make this experience public. She followed up this work with a series about survival and consolation. In Trostpflaster (2021), she cut and stuck medical plasters on canvases as a symbolic process of her own recovery. She also found that her trauma had a significant resonance with others, since many have shared similar stories with her on social media.

How to Remove Plasters with Pain, 2021. Exhibition view of a solo show in the context of the summer festival of the Shedhalle Tübingen e.V., 2021. Photo: Julie Legouez.

The act of disclosure has been an important tactic for feminist writers and artists to illuminate the link between private issues and systemic injustices. Feminist scholars also point out that class and gender-based inequality is often intrinsic to romantic relations. The sociologist Eva Illouz describes the “misery of love” as a result not only of prevailing patriarchal values, but also today’s impossible romantic ideals.2 In Hanging on the Past (2022), a work inspired by Illouz’s work, Legouez compiles familiar images of the “one, great love,” found in films and series she grew up with. “These films always tell the same stories, and they have nothing to do with reality,” she concludes. Although they can easily be written off as childish or cliché, these stories are symptomatic of a dominant romantic ideal, i.e. finding a partner, getting married, having kids.

Red Flags (You are too sensitive, I did it because I love you, I never said that), 2022. Exhibition view: Culterim, Gallery Culterim, Berlin, 2022. Photo: Julie Legouez.

Legouez’s insistence on linking the personal and the political places her in a legacy of feminist thinking. In the fall of 2022, she curated an exhibition at Culterim Gallery in Berlin, where she also did a residency, that exclusively featured the work of female and non-binary artists. Under the title “Dear Diary…”, the exhibition took up Legouez’s interest in the diary as an expression of the subjective and quotidian. It also served to initiate a creative network between the exhibiting artists. Legouez finds that patriarchal structures still largely determine the art world, which makes alternative and inclusive networks crucial. Furthermore, she sees a pressing need to create more awareness of sexism and gender inequality within our culture at large. Especially when it comes to romantic love, we are often oblivious to gendered power structures. Manipulative behaviour and jealousy are frequently portrayed as romantic instead of signalling a red flag. After her own experience of an abusive relationship, she encourages calling out sexist and violent behaviour for what it really is.

Legouez’s work paints a dark image of love, but she never shames or condescends to herself or others for being caught up in desires and relationships that do not always end happily or that bring great pain. Her work exposes harmful patterns of our private lives, but also gives opportunities to process past traumas. Staying with the trouble that love yields, she lets us reflect on love’s shortcomings without losing sight of the desiring subject.

Josefin Granetoft studied Art History and Visual Studies at Lund University and is currently completing her MA in Art History at Freie Universität Berlin. She works as an art mediator at JSF Berlin and initiated the curatorial project para/text in 2022.

Julie Legouez was born in 1988 in Viersen, West Germany. She is a multidisciplinary artist living in Berlin, Germany. She studied painting in Berlin and Vancouver and participated in exhibitions in Germany, Canada and Italy. In 2022 she was part of the Culterim Residency and in 2023 she received the NEUSTARTplus grant from the Stiftung Kunstfonds.

1 Jaye Early, “Contemporary Confessional Forms and Confessional Art,” Third Text 36, no. 4 (4 July 2022): 370, https://doi.org/10.1080/09528822.2022.2074197.

2 Eva Illouz, Why Love Hurts: A Sociological Explanation (Cambridge, U.K.; Malden, M.A: Polity, 2012).