︎︎︎

EPHEMERAL POLYPHONY

Julia Lübbecke gathers different voices, forms of expression, and materials within her artistic practice to form temporary ensembles. This text mirrors their fragmented, non-hierarchical structure. There is no chronology; each part stands for itself; together, they form one portrait.

Text, screenshots, images, words, photos – acknowledging a variety of documented forms of expression, Julia Lübbecke uses numerous sources in her artistic research. Their composition and visual assemblage are precise yet surprising and make us wonder how they relate to one another and which meanings their proximity creates.

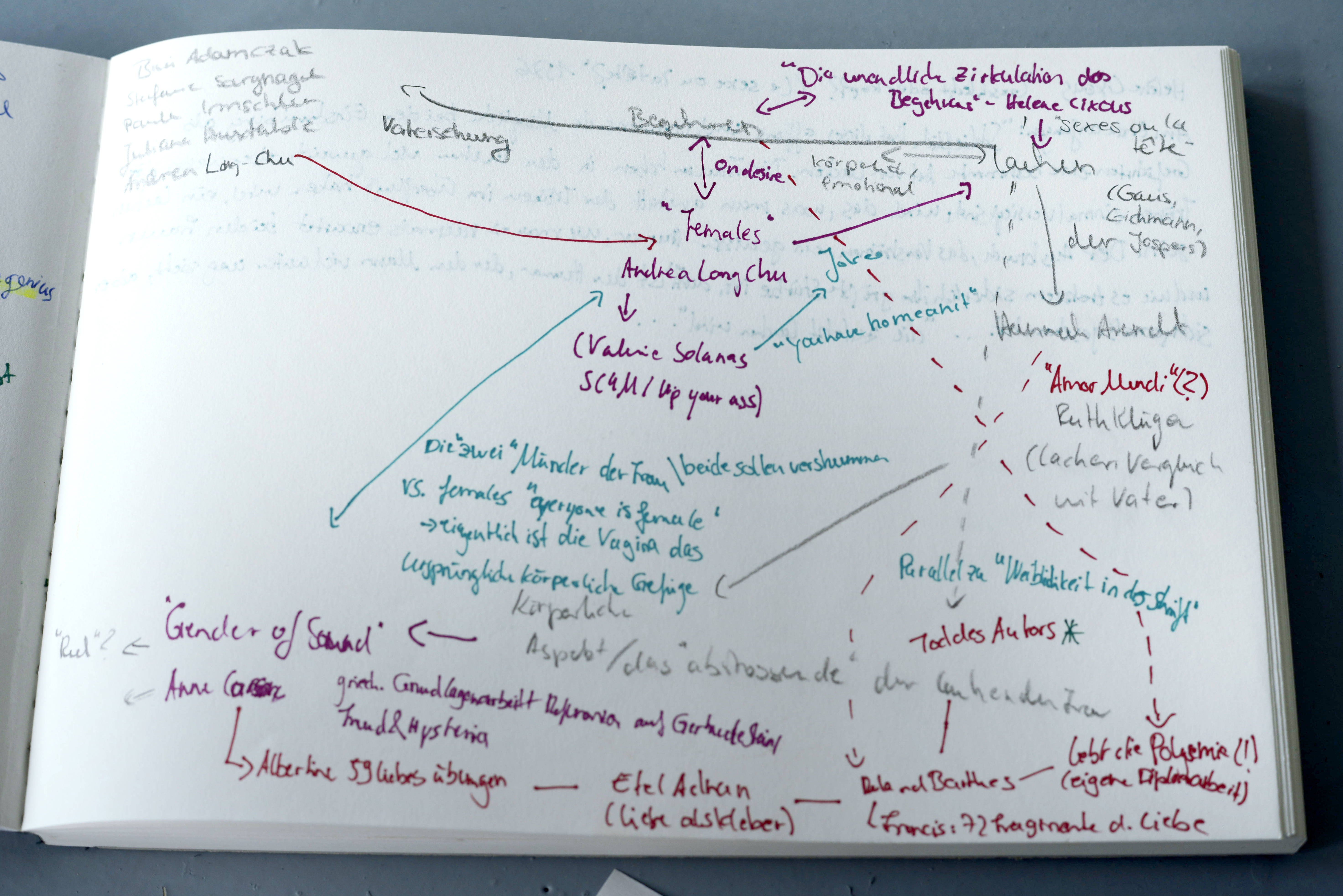

Julia refers to the basis for her artistic practice as ‘subjective archives’. Each thematic research starts with a polyphonic reading process, wherein the artist translates related narratives and associations into visual notes. This process is guided by her focus on situations, stories, and people usually not included in Western hegemonic storytelling. The subjective archives encompass authors from different backgrounds and various means of expression besides printed matter. Rejecting the idea of creating a structure for her research and the resulting archive, this thematic focus remains the primary selection mode. The archive is always temporary and in constant transition. The question of what is not captured during this continuous process is perpetually present. Overcoming classical archiving structures, Julia gathers all material in a digital folder sorted only by month. Each month’s folder is a juxtaposition of research results on various topics, references to a cultural image repertoire, and her own thoughts, conversations, texts, and notes all brought into affective proximity just through their date of encounter.

The different parts of Julia’s working process resonate with, frequently expand and – through their reciprocal and affective influence – shape the archival material. “The practical transformation of the content to be worked on takes place in a continuous recourse to the subjective archive. The handling and visualization become part of the work complexes,” she explains.

The vast material collection, each a partial archive in itself, is hard to navigate, neglecting the logic of browsable keywords or structures other than the temporal. Julia succeeds in curating knowledge in a very tangible way, and simultaneously questions the factual invisibility of knowledge curation in other forms of documenting and archiving practices. While her archive remains in a fluid and malleable state at all times, the installations mark moments of stillness within her practice. Every piece’s position is well thought out, documented through its own map and accompanied by an index listing each image’s origin, enabling the viewer to trace the artist’s thoughts.

The notion of revealing one’s sources allows us to follow the thought patterns which shape Julia’s artistic research and potentially guide the visitor’s further interests. Julia aims to overcome the conceptualization of the artist-as-genius by creating a closeness to other people’s thoughts, navigable through the work’s index. This enables exchange with people cited in the works or with the audience, which in turn resonates with and transforms her archive’s temporal status quo.

Julia refers to the basis for her artistic practice as ‘subjective archives’. Each thematic research starts with a polyphonic reading process, wherein the artist translates related narratives and associations into visual notes. This process is guided by her focus on situations, stories, and people usually not included in Western hegemonic storytelling. The subjective archives encompass authors from different backgrounds and various means of expression besides printed matter. Rejecting the idea of creating a structure for her research and the resulting archive, this thematic focus remains the primary selection mode. The archive is always temporary and in constant transition. The question of what is not captured during this continuous process is perpetually present. Overcoming classical archiving structures, Julia gathers all material in a digital folder sorted only by month. Each month’s folder is a juxtaposition of research results on various topics, references to a cultural image repertoire, and her own thoughts, conversations, texts, and notes all brought into affective proximity just through their date of encounter.

The different parts of Julia’s working process resonate with, frequently expand and – through their reciprocal and affective influence – shape the archival material. “The practical transformation of the content to be worked on takes place in a continuous recourse to the subjective archive. The handling and visualization become part of the work complexes,” she explains.

The vast material collection, each a partial archive in itself, is hard to navigate, neglecting the logic of browsable keywords or structures other than the temporal. Julia succeeds in curating knowledge in a very tangible way, and simultaneously questions the factual invisibility of knowledge curation in other forms of documenting and archiving practices. While her archive remains in a fluid and malleable state at all times, the installations mark moments of stillness within her practice. Every piece’s position is well thought out, documented through its own map and accompanied by an index listing each image’s origin, enabling the viewer to trace the artist’s thoughts.

The notion of revealing one’s sources allows us to follow the thought patterns which shape Julia’s artistic research and potentially guide the visitor’s further interests. Julia aims to overcome the conceptualization of the artist-as-genius by creating a closeness to other people’s thoughts, navigable through the work’s index. This enables exchange with people cited in the works or with the audience, which in turn resonates with and transforms her archive’s temporal status quo.

Looking at Julia Lübbecke’s installations, one wonders if this is a constant work in process. Big plasterboards, covered with all sorts of images, are strewn about the exhibition space. Sometimes leaning against the wall, at other times supporting one another, they build seemingly precarious yet firm structures. Their installation looks to be fugitive, almost as if at any minute someone will pick them up and carry them away. In comparison, the visual material presented on the boards or lying on top of them seems too profound and thoroughly selected to result from a temporary, random arrangement. The tension these subtle details of the installations create demands one’s full attention in order to uncover their complexity.

The plasterboard figures dissolve the white wall as a supposedly neutral space for presenting art, providing a different, pre-determined base for each work, and mirror Julia's practice through their material and form. Usually, plasterboard is used on construction sites, hidden within the walls to offer stability. By themselves, the boards are delicate. If they fell, they could break into pieces. This juxtaposition of strength and fragility within the material reflects the basic idea of Julia’s work: that one might become stronger by being fragile. Analogous to her working process, each structure's supposedly elusive set-up might seem accidental, but it is quite the opposite. Every piece’s position is planned, mapped, and constructed in detail. Just like her artistic research is based on the principle that no statement is definite – there is always new information to be found, associations to be made – the structures remain ephemeral and open in their temporary state.

Julia transforms her sources found in various media into visual information gathered on the plasterboards. She describes how, by working with such a variety of sources, “polyphonic works are created in which texts are used as text, texts as images, images as notes and images as images. The meaning of the subjective archive comes to the fore.” She captures quotes seen in exhibitions, books, or elsewhere on photos, adding a visual element to the written information. She transforms online videos into letters, turns them into statements spread out all over the plasterboards. No matter what form they took in the beginning – temporal or permanent, tactile or audible – they gain a visual quality within Julia’s work.

The plasterboard figures dissolve the white wall as a supposedly neutral space for presenting art, providing a different, pre-determined base for each work, and mirror Julia's practice through their material and form. Usually, plasterboard is used on construction sites, hidden within the walls to offer stability. By themselves, the boards are delicate. If they fell, they could break into pieces. This juxtaposition of strength and fragility within the material reflects the basic idea of Julia’s work: that one might become stronger by being fragile. Analogous to her working process, each structure's supposedly elusive set-up might seem accidental, but it is quite the opposite. Every piece’s position is planned, mapped, and constructed in detail. Just like her artistic research is based on the principle that no statement is definite – there is always new information to be found, associations to be made – the structures remain ephemeral and open in their temporary state.

Julia transforms her sources found in various media into visual information gathered on the plasterboards. She describes how, by working with such a variety of sources, “polyphonic works are created in which texts are used as text, texts as images, images as notes and images as images. The meaning of the subjective archive comes to the fore.” She captures quotes seen in exhibitions, books, or elsewhere on photos, adding a visual element to the written information. She transforms online videos into letters, turns them into statements spread out all over the plasterboards. No matter what form they took in the beginning – temporal or permanent, tactile or audible – they gain a visual quality within Julia’s work.

Julia Lübbecke’s works are concerned with the (in)visible. Facts, thoughts, identities that cannot be seen but are transformative forces within our society. In documenting and structuring knowledge, the question of what remains (in)visible is always up in the air. It affects fundamental questions of what is captured in which medium, and more specific questions of selecting content worthy or negligible of documentation. It is a contingent process.

Archives still have an aura of objectivity, supposedly transporting authentic narratives and information of the past into the present. The usual design of an archive requires keywords and browsable content of some form, which naturally excludes some material. Certain content is neglected as it is not deemed meaningful. Through her contemplative archival mode of working, Julia breaks with this perception and reveals unseen hierarchical documentation structures.

She gathers an array of material and converts their format to reference other material, enabling an affective symbiosis of meaning: for example, online video-clips from the internet’s early days, existing in a digital wasteland. In theory, they are accessible to everyone. However, in practice they are hard to find since they are not linked to search engine optimized keywords and do not come with an online presence advertising for them. One source for Julia’s latest work With the Gloves off, which evolves around the notion of desire, is an online video of a speech by Sylvia Rivera. Rivera was a Latina transgender activist who managed to get on stage during the 1973 New York City Gay Pride rally and addressed the factual entanglement of class with race and gender, often ignored within the gay rights movement. Enraged, she addresses the extreme violence trans people face while also having to deal with higher rates of unemployment, homelessness and incarceration. Rivera pleads with the mainly white, middle-class audience to show solidarity, support trans and BIPoC communities and develop a more inclusive political movement. Despite growing attention to the speech, it has not been documented in any other form but the recording. Julia worked with screenshots of the video but also transcribed quotes. Through big letters across the installation, parts of the speech become available in a written form, opening up possibilities of closeness for Rivera's words to other media, audiences and interpretations outside of the digital sphere.

Anything collected in archives is tied to hierarchical societal structures in favor of those who have built them. Julia’s practice is perpetually concerned with the (in)visible that underlies societal interaction and does not benefit from the oppressive structures forming our reality. Working with an intersectional, queer feminist perspective, she states that one cannot think about sexual orientation, bodies, or identities without addressing class. In With the Gloves off, this entanglement becomes visible through recourses to the body and skin. Once the gloves are off, all protection vanishes. People fight with their bare hands. Their body, their skin, their personal stories are in the midst of a political fight, and class is a decisive factor in who has to fight with or without protection. People’s dreams, desires and hopes become all the more visible. All those who long for societal change have to fight with their gloves off. This creates a moment in which they are both more vulnerable and exposed, yet simultaneously strengthened and aware of the transformative power they wield.

Archives still have an aura of objectivity, supposedly transporting authentic narratives and information of the past into the present. The usual design of an archive requires keywords and browsable content of some form, which naturally excludes some material. Certain content is neglected as it is not deemed meaningful. Through her contemplative archival mode of working, Julia breaks with this perception and reveals unseen hierarchical documentation structures.

She gathers an array of material and converts their format to reference other material, enabling an affective symbiosis of meaning: for example, online video-clips from the internet’s early days, existing in a digital wasteland. In theory, they are accessible to everyone. However, in practice they are hard to find since they are not linked to search engine optimized keywords and do not come with an online presence advertising for them. One source for Julia’s latest work With the Gloves off, which evolves around the notion of desire, is an online video of a speech by Sylvia Rivera. Rivera was a Latina transgender activist who managed to get on stage during the 1973 New York City Gay Pride rally and addressed the factual entanglement of class with race and gender, often ignored within the gay rights movement. Enraged, she addresses the extreme violence trans people face while also having to deal with higher rates of unemployment, homelessness and incarceration. Rivera pleads with the mainly white, middle-class audience to show solidarity, support trans and BIPoC communities and develop a more inclusive political movement. Despite growing attention to the speech, it has not been documented in any other form but the recording. Julia worked with screenshots of the video but also transcribed quotes. Through big letters across the installation, parts of the speech become available in a written form, opening up possibilities of closeness for Rivera's words to other media, audiences and interpretations outside of the digital sphere.

Anything collected in archives is tied to hierarchical societal structures in favor of those who have built them. Julia’s practice is perpetually concerned with the (in)visible that underlies societal interaction and does not benefit from the oppressive structures forming our reality. Working with an intersectional, queer feminist perspective, she states that one cannot think about sexual orientation, bodies, or identities without addressing class. In With the Gloves off, this entanglement becomes visible through recourses to the body and skin. Once the gloves are off, all protection vanishes. People fight with their bare hands. Their body, their skin, their personal stories are in the midst of a political fight, and class is a decisive factor in who has to fight with or without protection. People’s dreams, desires and hopes become all the more visible. All those who long for societal change have to fight with their gloves off. This creates a moment in which they are both more vulnerable and exposed, yet simultaneously strengthened and aware of the transformative power they wield.

Julia Lübbecke embraces the confrontation with her own identity as a white female artist, a confrontation which is inevitable as part of a reflection about societal power structures in her artistic practice. Even after decades of activism, women are still facing various disadvantages in the art world. We are far away from overcoming the need for feminist artistic practices. Yet not only gender, but also race or class often determine artistic success, influencing who gets a platform and a voice within (the artistic) society. In the face of oppressive structures denying groups of people representation, Julia saw it as concomitant to follow intersectional and queer feminist approaches. Instead of solely improving the situations of white female artists, she aims to destabilize the oppressive system itself.

She concludes that knowledge is under constant revision and, at times, needs to be re-evaluated. Expanding her personal canon of literature, theory, art and history, she has been engaging with multiple global feminisms since 2015. The extensive political approach informing her artistic practice addresses the complicated process of conceding to an identity category in favor of representation without challenging the ailing system of oppression. Julia seeks to destabilize the norm but, at the same time, acknowledges that the political status quo still requires identity politics.

“In my opinion, one of the main goals of queer feminist politics and its advocates is to find provocative forms of reinterpretation of difference that continually oppose a classificatory logic of domination,“ she explains. This desire for reinterpretation resonates in her practice of critical appropriation. She succeeds in amplifying a polyphony of voices in the battle, composed of struggles related to her own identity as either the oppressed as well as part of the oppressing system, without implying that these battles are equal. She assembles various voices, thereby visualizing blank spaces in the constant destabilization battle.

A process of self-reflection is a constant element of her political practice. This approach means taking a step back and listening to those in need of support. It means carefully choosing which funding to apply for, where to show one’s art and how to support others with the platform already available to oneself. It can mean to enter into a dialogue with those ready to learn and to become allies. Sometimes it can mean to include in one of her installations a specific voice that is often overlooked.

At other times, it means to not touch a topic, since showing solidarity might entail speaking for a group whose voice she could inadvertently drown out. The lines are thin, sometimes blurry, and the process always requires thorough navigation. But through her intriguing works, Julia Lübbecke not only succeeds in curating knowledge but, through her visual language, makes this process more transparent and lets us become part of it.

She concludes that knowledge is under constant revision and, at times, needs to be re-evaluated. Expanding her personal canon of literature, theory, art and history, she has been engaging with multiple global feminisms since 2015. The extensive political approach informing her artistic practice addresses the complicated process of conceding to an identity category in favor of representation without challenging the ailing system of oppression. Julia seeks to destabilize the norm but, at the same time, acknowledges that the political status quo still requires identity politics.

“In my opinion, one of the main goals of queer feminist politics and its advocates is to find provocative forms of reinterpretation of difference that continually oppose a classificatory logic of domination,“ she explains. This desire for reinterpretation resonates in her practice of critical appropriation. She succeeds in amplifying a polyphony of voices in the battle, composed of struggles related to her own identity as either the oppressed as well as part of the oppressing system, without implying that these battles are equal. She assembles various voices, thereby visualizing blank spaces in the constant destabilization battle.

A process of self-reflection is a constant element of her political practice. This approach means taking a step back and listening to those in need of support. It means carefully choosing which funding to apply for, where to show one’s art and how to support others with the platform already available to oneself. It can mean to enter into a dialogue with those ready to learn and to become allies. Sometimes it can mean to include in one of her installations a specific voice that is often overlooked.

At other times, it means to not touch a topic, since showing solidarity might entail speaking for a group whose voice she could inadvertently drown out. The lines are thin, sometimes blurry, and the process always requires thorough navigation. But through her intriguing works, Julia Lübbecke not only succeeds in curating knowledge but, through her visual language, makes this process more transparent and lets us become part of it.

Laura Seidel is currently writing her Master's thesis on structures of intersectional discrimination in the arts at the institute for Art History at FU Berlin. Her research interests include queer feminist approaches to art history and art institutions, sociology of art, space art and the planetary. Laura has worked as an art educator in numerous Berlin art institutions and is currently the host of a monthly conversation series at ZAK (Zentrum für aktuelle Kunst, Berlin). Laura also works in a curatorial duo with Kira Dell and is part of CCCCCOMA collective.

Julia Lübbecke (*1989 in Gießen) studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, at UMPRUM - Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague and at the Academy of Fine Arts in Leipzig, where she graduated in 2019 with Peggy Buth, Tina Bara and Dr. Christina Natlacen. Her works have recently been shown at ZAK Center for Contemporary Art in Berlin, IKOB - Museum of Contemporary Art in Eupen (BE), Vunu Gallery in Košice (SK) and at Rencontres d'Arles (FR). She was awarded with the IKOB - Art Prize for feminist art in 2019 and is currently one of the participants of the postgraduate program Goldrausch Künstlerinnenprojekt. She is part of the collective Law of Life and currently lives and works in Berlin.

Julia Lübbecke (*1989 in Gießen) studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, at UMPRUM - Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague and at the Academy of Fine Arts in Leipzig, where she graduated in 2019 with Peggy Buth, Tina Bara and Dr. Christina Natlacen. Her works have recently been shown at ZAK Center for Contemporary Art in Berlin, IKOB - Museum of Contemporary Art in Eupen (BE), Vunu Gallery in Košice (SK) and at Rencontres d'Arles (FR). She was awarded with the IKOB - Art Prize for feminist art in 2019 and is currently one of the participants of the postgraduate program Goldrausch Künstlerinnenprojekt. She is part of the collective Law of Life and currently lives and works in Berlin.