︎︎︎

Silicone Meme

washable images & sampled tropes

Carlotta Lücke’s semantics of the everyday float in circulation

by Imke Gerhardt

Out of the tension between the general and the particular, between the relatable and the singular, the meme arises. In the orbit of its fast circulation, an imagined community can be temporarily found. An ephemeral interpersonal cohesion, generated by an ongoing dispersion. Borderless, the meme relieves legibility from its spatial confinement, giving the subject space for intuitive affirmation: #it me. The liberal fetish of individuality is thus paired (again) with a longing for universality, making the unique subject happily identify with the stock photo. In search of this short moment of communal affiliation, the isolated individuals browse the virtual space, in which they’re usually obliged to ceaselessly perform their singularity.1 Sharing memes, sharing everyday tropes is the lonely becoming of the self and the other, in their precarious relation.

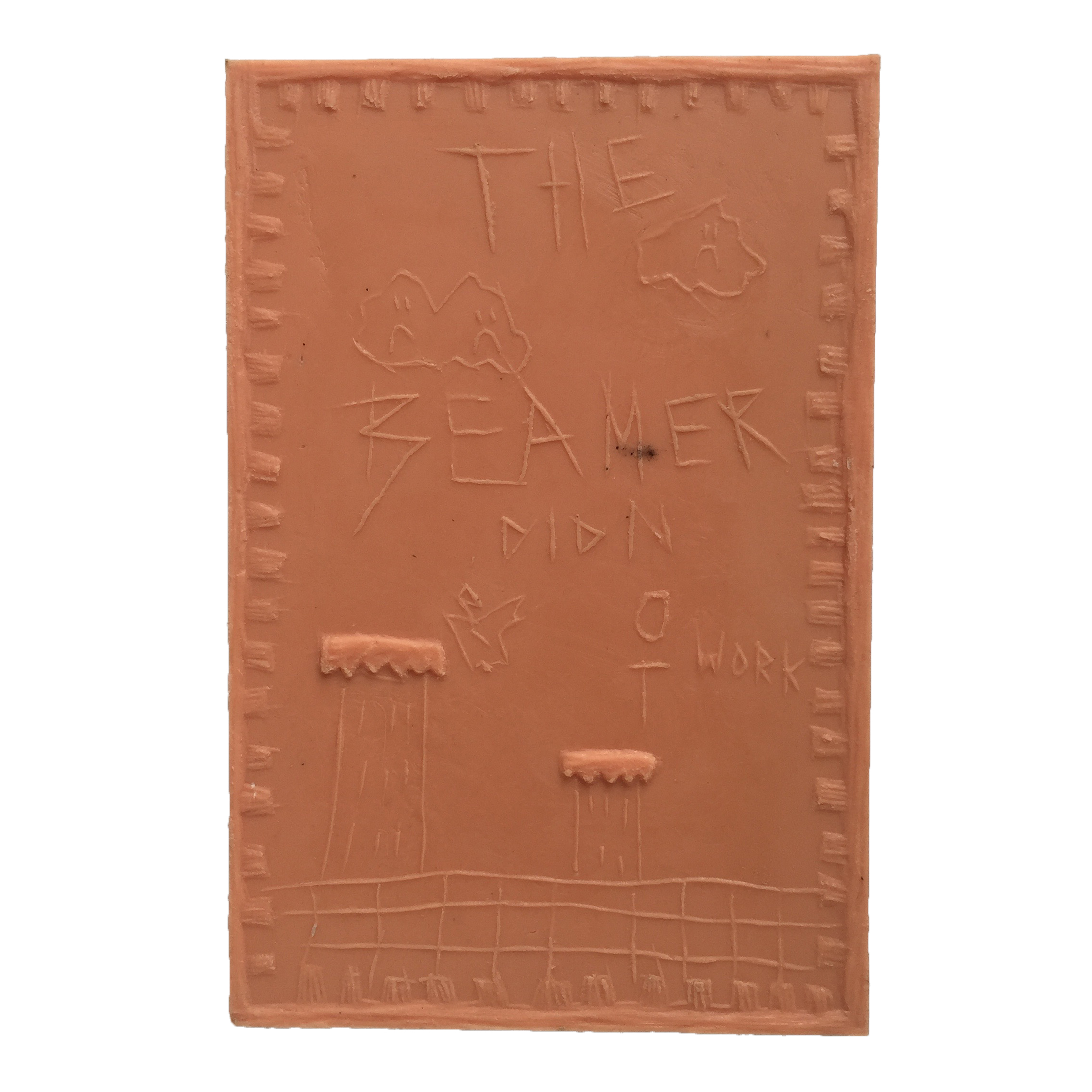

The beamer did not work, 2021, 33 x 21 cm.

He brought his tomato paste from home (2021) and The beamer did not work (2021) are the titles of Berlin-based artist Carlotta Lücke’s recent works. Small (33x21cm), salmon-coloured composites, made out of MDF boards and silicone. To create these, Carlotta first carves her drawings into the MDF boards to then fill the removed parts with liquid silicone (inverted woodcut). Before hardening, she presses another MDF board on top, to make it the new backside of the work. After the silicone between the boards has solidified, she removes the front board, the negative, to obtain the positive, the new silicone imprint of the drawing, sticking to its wooden backside. Because of the lack of perspectival depth and the addition of words, text, and smileys, the works’ appearances resemble children’s drawings, in which one can encounter sad clouds, or short phrases, picked up from everyday experiences. The respective titles, written in uneven capitals, are integrated into, or rather constitutional elements of the works, as they’re taking up much space in each drawing. The combination of a short trope, pulled out of the everyday and a ‘simplistic’ image make them resemble (macro-)memes, or, as I call them, analogue memes. Like digital ones, analogue memes are erratic in their clarity and complex in their ‘two-dimensional’ flatness. Both only appear relatable to us, because of shared cultural codes, which are equally responsible for making the surface of our everyday (commonly) legible.2

The naturalness of the everyday surrounding us and the authenticity of the given self are both an effect of their imperceptible co-constitution; of their dynamic mutual becoming in a specific time and space. Internalised (in)formal norms regulate our social togetherness. Embodied societal rhythms simulate the objectivity of time. We are guided through material and virtual infrastructures, in which our visual axis gets aligned in the ‘right’ angle to the hegemonic discourse. The everyday is a synthesis, a dynamic mesh of relations. Formerly geographically and temporally encoded, the quotidian in the digital age is uncoupled from time zones and spatial limits.

Silicone is a synthesis, too. An anomalous hybrid of an inorganic structure and a remaining organic part. Its wide use is a consequence of its flexible morphology. Rubber or liquid, lipids, or resin. Like MDF boards, silicone is the epitome of mass production and symbol of a functional modernity. In these embodiments of industrial manufacturing, which leave such an (ecological) imprint on our everyday living, Carlotta now carves in her synthetic and composed scenes of the everyday, using a print-making technique. Her depictions are sampled, a compilation of collected experiences, referring to the many temporal layers of the present.

@carlottasoriginals, 17.04.2021

https://www.instagram.com/p/CNwyuSdDy4b/

In daily life, the illusory idea of a linear time collapses, as traces of the past traverse our present and haunt our future. This becomes clear in regard to the ecological consequences of industrialisation, which shape the look of our future world already today. It is an irony that the silicone, which Carlotta uses to make a print of the temporal layers of the quotidian and which has in its industrial production an imprint on the ecosystem, can itself evade the inscription of time. The functional and sterile silicone is easily washable. Its surface can be cleaned of dust, which has fallen over time.

Sooner or later, the time has come and the first dust particles have accumulated on your drawing. Today I’ll show you what you can do in a situation like this: You just use a sponge and water. If you want you can also use some dish soap—and then carefully clean the drawing. A small hint: be careful with the corners to avoid that the silicone comes off the wood. And this is how you clean your silicone drawings.

In this one-minute tutorial posted on her Instagram page, @carlottasoriginals, where many of her artworks are for sale, the artist explains the correct handling of her drawings. Mocking convention, Carlotta confidently washes her work, that which is meant to be handled with care. That an artist has no fear of contact with their artwork should be of no surprise. The sublimation of the artwork, which turns it into an untouchable, sacred object usually happens after the mystified process of creation. The viewers, along with their internalised fear of contact, express their respect for the holy object by keeping an adequate distance to its aura.3

This can be seen as a performance in itself, making it clear that ‘aura’ is not an essence, but an elusive in-between. Aura is an effect of the fabricated relation between the staged artwork in the holy white cube and the normalised behaviour of the viewer. Aura is thus simply the result of a performative act.

This is my understanding of the Aura and not the way Walter Benjamin famously defined it in his essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1936). Especially, I disagree with his assumption that traditional as well as modern techniques of reproduction cause a loss of the Aura. Rather, the Aura is immediately (re)established as soon as the reproduction is appropriately staged and reverently faced.

Carlotta is using a traditional reproduction technology, yet produces only one copy, the original. Maybe aware that even the Multiples of the 60s, which were initially produced in high quantities to reject the priceless (and therefore high-priced) unique artwork, could themselves in the end not escape the adding of value, Carlotta dismisses the option to make more than one silicone ‘print’, even if that could increase her profit. At the same time, she equally rejects the fetishization of the original by treating her work as an everyday object. The washing of the surface of an artwork is, due to Western modernity’s conservation mania, the ultimate offence. That this wasn’t always considered an insult becomes clear by taking a look at a past, in which it was a common practice to paint over or trim paintings when they were unsatisfactory/inadequate. Think for example of Sir Joshua Reynolds' changes in the paintings of Rembrandt. Moreover, I also wonder: isn’t it paradoxical that the meticulous conservation of art and the infinite storage of data has such an immense energy consumption, that the earth will perish sooner or later in the face of the West’s pedantic conservation?

The untouchability of artworks—an historically-specific societal norm—is not only required to produce, or less provocatively, intensify the artwork’s Aura. It is certainly also necessary for its conservation. To preserve a past time requires the artificial elimination of a constant (natural) inscription of time—the fingerprint’s imprint of its presence. Carlotta’s approach differs. Instead of protecting the surface from time to create the timeless sacred object, she washes the surface meticulously to keep it clean from temporal markers.

He brought his tomato paste from home, 2021, 33 x 22 cm

Since its beginning, capitalism did well in staging the uniqueness of the sacralised artwork for the purpose of an excessive extraction of profit. Yet it managed not only to benefit from the production of singularity, but from high quantities alike. Capitalism’s mastery of any reproduction technology finds an exemplary expression in what was in the 20th century derogatorily called cultural industry. In the 21st century, in the Age of Digital Reproduction, the act of copying took on a whole new importance. Both on a surface and subsurface level, the internet is based on linking and copying. Its infrastructure is built on sharing, retweeting, and re-blogging. Thus its net matrix is relying on the feeling of relatability, such as memes. Indeed, when interviewing Carlotta about her work, she referenced memes herself, yet wouldn’t directly relate her drawings to them. The interlacing of image and text (macro-meme), the reduced character of the drawings, and the use of everyday tropes make the use of the term still seem very plausible to me. Yet memes are usually created with the intention to generate maximum relatability: to go viral. Carlotta’s analogue meme (without further copies) can hardly go viral, as virality would require their mass production and a drastically accelerated global distribution. However, to use a time-consuming, traditional method, by which the ordinary scenes are being carved into the wood—an anachronistic materialisation of permanence and stability, actually very antithetical to the immaterial ephemerality and speed of internet (memes)—is not to be understood as a reactionary counter-movement, wishing to go back to pre-digital times. It’s not a Heideggerian gesture, not an attempt to re-root in a mystified earth and a bygone time, as the materials Carlotta uses are themselves products of organised modernity. Silicone and MDF boards symbolise a standardised and an already-accelerated mass production. By additionally uploading her works on Instagram, the artist not only rejects the illusion that a clear separation between online and offline is still possible, but also objects to a new romanticisation of the offline as a real, authentic counter-place. This is an important rejection as capitalism was always very brilliant in creating potential oases allegedly outside the system, to stabilise its core: free time (to work better), tax exiles, the art world, etc. The exceptional value principles of the latter, which are legitimised by the scarcity of the creative products and the romanticisation of the artist-genius, helped capitalism to survive any crises, as the latest financial crash of 2008 proved.

Art and the artworld are not outside Capitalism, but an integral part of it. Artworks help capital investments and the creative role of the artist now serves as the primary role model for the individual in Western society. Creativity and singularity as the new norms call for a relentless staging and marketisation of the self. There’s no permanent employment, but temporary contracts, no stability but a call for flexibility, which push the subject into the new insecurity of a project-based working life. The quantifiable recognition, which this lifestyle provides online, is unable to compensate for the lack of monetary reward offline. The depressed and anxiety-driven subject forms the diseased synthesis of these allegedly separated spheres. Online it’s the internalised diktat of creative self-representation and the quantifiability of its success, which makes the subject’s unstable self-esteem depend on volatile market resonance. Offline it’s the existential anxiety, the material struggle, which this uncompensated lifestyle brings about.

Carlotta shows awareness for the inescapability of the capitalist logic which incorporates what claims to be outside. On all levels the artist mocks the conditions which produce the enclave in the first place. By uploading her work, she ridicules the original, whose digital reproduction slips out of her control. By providing humorous tutorials, showing how to wash the artwork’s holy surface, she debunks its mystification as untouchable singularity. And by clearly playing with the coercion to marketize the self and—inseparably connected—one’s work, she exposes the precarity of the modern creative subject. In that regard, Carlotta’s choice of technique has to be seen as an ingenious comment on contemporary society as well. Overstressed by the constant self-marketisation, the individual nowadays hopelessly tries to find some sense of authenticity by partly turning offline: a temporary digital detox, or even a return to handcraft. By time-consumingly carving her drawings into wood, she is countering the chronic pain of lacking time in an accelerated world, consciously taking/making time through a slowed down working process. The immateriality of one’s virtual everyday, overworking the eyes, is answered by tactile hand-work.

However, socialised by social media, and thus addictively depending on its reward system, offline mindfulness seems to be only celebrated in society if there’s the option to share and present it again online. Or can we even go so far to say that the internalised Instagram frame shapes the experience before it is taking place? Either way, these new models of the visual infrastructure dominantly define the perception of an everyday, which is presented in its unattainable perfection in square cut-outs.

Carlotta’s similarly curated scenes of the everyday have to be poured into models—yet anachronistic ones—as well in order to become visible. This is a double stroke of genius as the artist not only shows that the alleged clarity and authenticity of the offline everyday is equally only the product of her weaving together cultural codes of different times and spaces, but also that the offline everyday can’t be instrumentalised as the romantic counter-place against the inauthentic online everyday for exactly that reason. Carlotta plays with the illusion of authenticity, with the naturalness of the offline everyday which in its immediacy conceals its conditional layers and hides its underlying models, which frame what we see. Her drawings appear spontaneous and arbitrary, but are actually highly composed, based on a laborious selection process, where others are also involved in conversation, themes are developed, and everyday tropes are collected, sampled, and reworked over time. The outcome is an assemblage consisting of temporal and spatial layers which all together condition that which we see: the simple drawing, the surface of the everyday.

Digital memes are assemblages, too. They are sliding set pieces, confusing time and space. They are shared references drawn from a borderless collective archive, which they help to saturate at the same time. Collectively shared, yet personally relatable, the meme debunks the inevitable meshing of individual and society, private and public, in the moment it goes viral. Carlotta’s analogue meme is only produced once, which drastically limits the chance for virality. Yet by uploading the works online she gives up the control of their reproduction. Reproduced now is their image, the artwork’s derivative, which becomes independent from its wooden model—a model which Carlotta made pulling cultural references, collective stories, and shared experiences together. The liquid silicone of the early stage has solidified, producing a readable image as its outcome. In a way this symbolises the creation of meaning, which equally needs to harden within cultural models of a specific time and space to become collectively understandable.

The meaning of Carlotta’s work never becomes stiff, but stays stretchy and easily washable. It is a colourful play from which all the dogmatics of the everyday can be rinsed off, again and again.

Imke Gerhardt studied Politics and Art History at Freie Universität Berlin, where she’s currently finishing her Masters in Art History. Focussing mainly on Modern and Contemporary Art, Media and Performance, Imke is interested in the entanglement of power relations and visual regimes. As a dancer she especially likes to question the latters effect on the body, its ways of expression and perception. Very much attracted to poetry, too, Imke likes to explore a more experimental style of academic writing, believing that a critique can just take effect, when the structure of language and communication is challenged, where ideology resides.

1 This paragraph and especially the idea of communities being created due to the relatability of memes was inspired by Aria Dean’s text Poor Meme, Rich Meme, published in Real Life Magazine, 2016.

2 By this I simply mean that the legibility and understanding of a (virtual) meme already requires some sort of a shared cultural knowledge, like a shared visual archive etc. The same goes for understanding everyday life in a society, which is the reason why one needs some time to adjust to living in a different culture. Carlotta’s analogue memes, which portray everyday scenes, thus combine both: online & offline cultural vocabulary, which you can only understand if you formerly shared the same cultural codes (online & offline).

3 The word ‘aura’ refers to Walter Benjamin and his work The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, 1936.