︎︎︎

The Practice of Everyday Life

by Congle Fu

Tang Han’s works offer a sense of pleasure, like having a conversation with a friend who is particularly skilled at playful yet revelatory inquiry. Her works always start from the subtle things she observes in everyday life or a question she raises in response to a common phenomenon that we all take for granted or simply ignore. The video work Pink Mao (2020) was inspired by a conversation between Tang and her friends. During the conversation, Tang found out that her friends thought the one-hundred-yuan banknote of China is red, but it is in fact closer to pink. However, despite this “fact,” people in China would probably still use the term hongse maoyeye 红色毛爷爷 (red grandpa Mao) to refer to the bill. It seems that the nature of the one-hundred-yuan bill is tied to the color red. Tang’s research begins with this observation, and she examines how the color red might be associated with the (actually pink) banknote in China as well as the change in and representation of the image of the banknote in the context of China’s social and economic development.

Questions raised by Tang in her work are seemingly innocuous but surprisingly searching. Some of Tang's questions may have an answer; others may be open ended. For instance, why is the color pink that stereotypically represents femininity connected with the masculine portrait of an important male leader? Given that cash payment has mostly been replaced by electronic payment in China, she wonders about this development’s effect on Mao’s image.1 Payment scanners only identify a flat digital code, not the portrait of the Great Leader. As the banknote with Mao’s portrait increasingly disappears from everyday life, reduced to mere binary digits circulating in the economy, will Mao’s image become invisible as well? This line of inquiry resonates with Deleuze’s proclamation of the dividual. For Deleuze, individuals in the digital age have become “banks” or data; the Great Leader is perhaps no exception.2 Will the detachment of Mao’s representation from the banknote gradually cause his image to disappear from the memory of the Chinese public?

Tang Han, Pink Mao, 2020, HD, color, sound, 22’30’’, still.

Courtesy of the artist.

Tang’s investigative process in Pink Mao strikes one as being exceptionally rational: facts are narrated, evidence is found, objective events are juxtaposed by the artist. Furthermore, she encloses reflections and provokes discussion. Tang essentially presents her audience with a research project she made by employing images. Such a methodology recalls that of the late filmmaker and video artist Harun Farocki, who engaged with his subjects of research by investigating images. Tang’s essay films, which are strongly influenced by Farocki’s aesthetics of images, take a different approach. Tang does not discuss war, the military, drones, or crimes; rather, she sifts through seemingly minor experiences she perceives in everyday life. Pink Mao’s questioning of whether the one-hundred-yuan bill is red or pink is a strange but exceptionally rational question, because while the association of the banknote with the color red is something habitual that no one would typically give a second thought to, one immediately finds the subtle observation to be true.

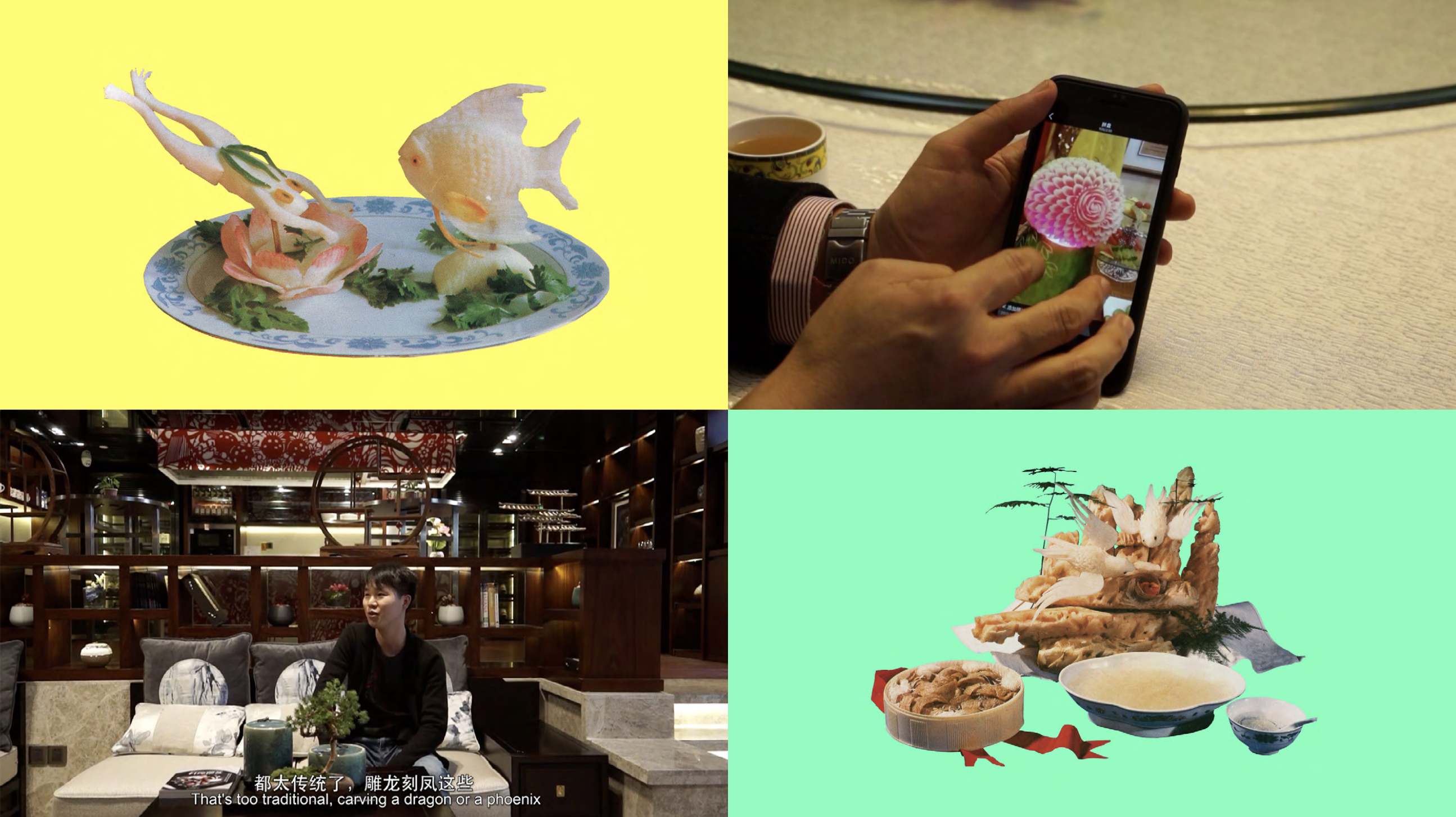

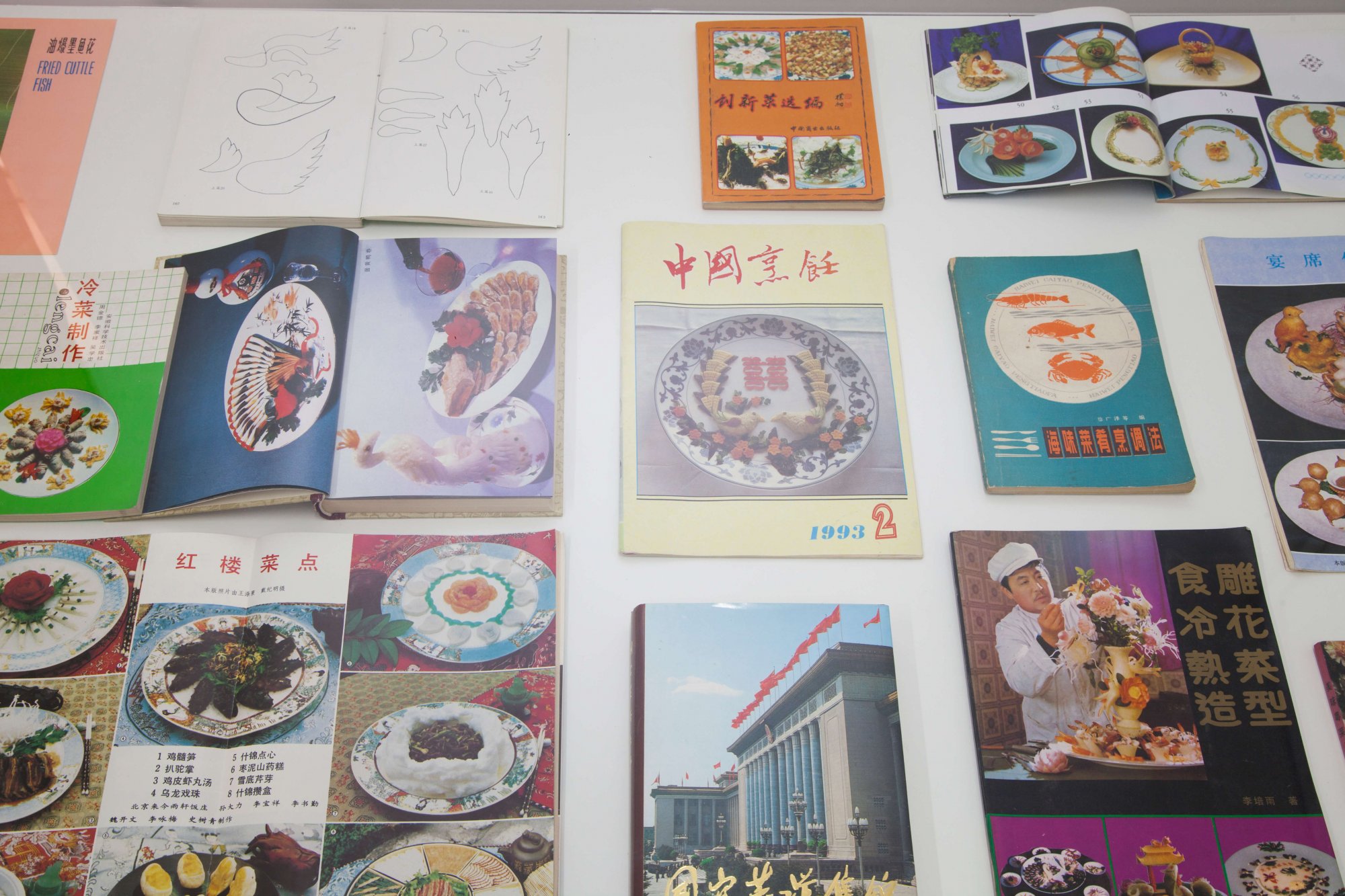

The observation of the everyday can also be seen in Tang’s other works. Guangdong people give people from other cities the impression that they are passionate about life and that food culture is an important part of the Guangdong region. Born in Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong, it seems rather natural or logical for Tang to create a work about food. In Shape of Appetite (2017), a project consisting of video, wallpaper, books, and magazines co-created by Tang and Zhou Xiaopeng, Tang and Zhou investigate the origins and changes in the aesthetics of plating in Chinese culinary culture. Both artists grew up in Guangzhou in the 1980s, and their dinner tables used to be decorated with a variety of beautifully sculpted dishes. This culinary aesthetic has since disappeared to be replaced by a minimalist presentation similar to that of Western cuisine. Tang and Zhou locate the importance of food carving in the description of diaoluan 雕卵 (the carving of patterns on eggshells) in the collection of philosophical essays Guanzi: Chimi 管子·侈靡 (Spring and Autumn Period, ca. 771 to 476 BCE). Carving on food is historical and expresses the human desire for aesthetics based on the abundance of food. Through interviews with restaurant professionals of different ages, Tang and Zhou also learned about the changes in food carving and plating over the past thirty years, from the employment of huawang 花王 (“flower kings”—chefs who specialize in food carving) to the dramatic transformation of the restaurant industry due to the influence of Western cuisine on plating. In the aesthetic changes of food presentation, one sees globalization and the intersection of different cultures.

Tang Han, Shape of Appetite, 2017, single-channel video, color, sound, 29’, still; and exhibition view, Bi-City Biennale of UrbanismArchitecture (UABB), Shenzhen. Courtesy of the artist.

Through the presentation of food in Shape of Appetite, one easily perceives the fact that culture is fluid. Indeed, Tang’s works, taken together, are evidence of this fact, although none of them are biased toward cultural fluidity. Her first video work, Pretties! Make Up! (2017), shows the hybridization of cultures and its impact on her. The Japanese anime series from the 1990s, Sailor Moon, was introduced to Hong Kong television in 1994, and the main figure of the anime, Tsukino Usagi (Sailor Moon), became the motif of Tang’s childhood drawings. One of the questions that Tang discusses in this work is the influence of popular culture on the masses, as Sailor Moon influenced Tang’s feminine aesthetic as well as that of the entire East Asian region. This reflects the great fluidity within East Asian culture and beyond. Modern communication technologies from the 1980s on have connected the world in an unprecedented way, and it seems everything since has become part of one enormous web. But the world was never isolated. Guangzhou, where Tang was born, was one of the major cities along the Maritime Silk Road and has been an important area for various intercontinental and global trade events since ancient times, and it continues to be part of a flourishing cultural interchange today. Hybridity and diversity are embedded in Tang’s identity, and they strongly affect the aesthetic of her works.

Tang Han,

Pretties, Make Up!, 2017, single-channel video, color, sound, 1’52”, still.

Courtesy of the artist.

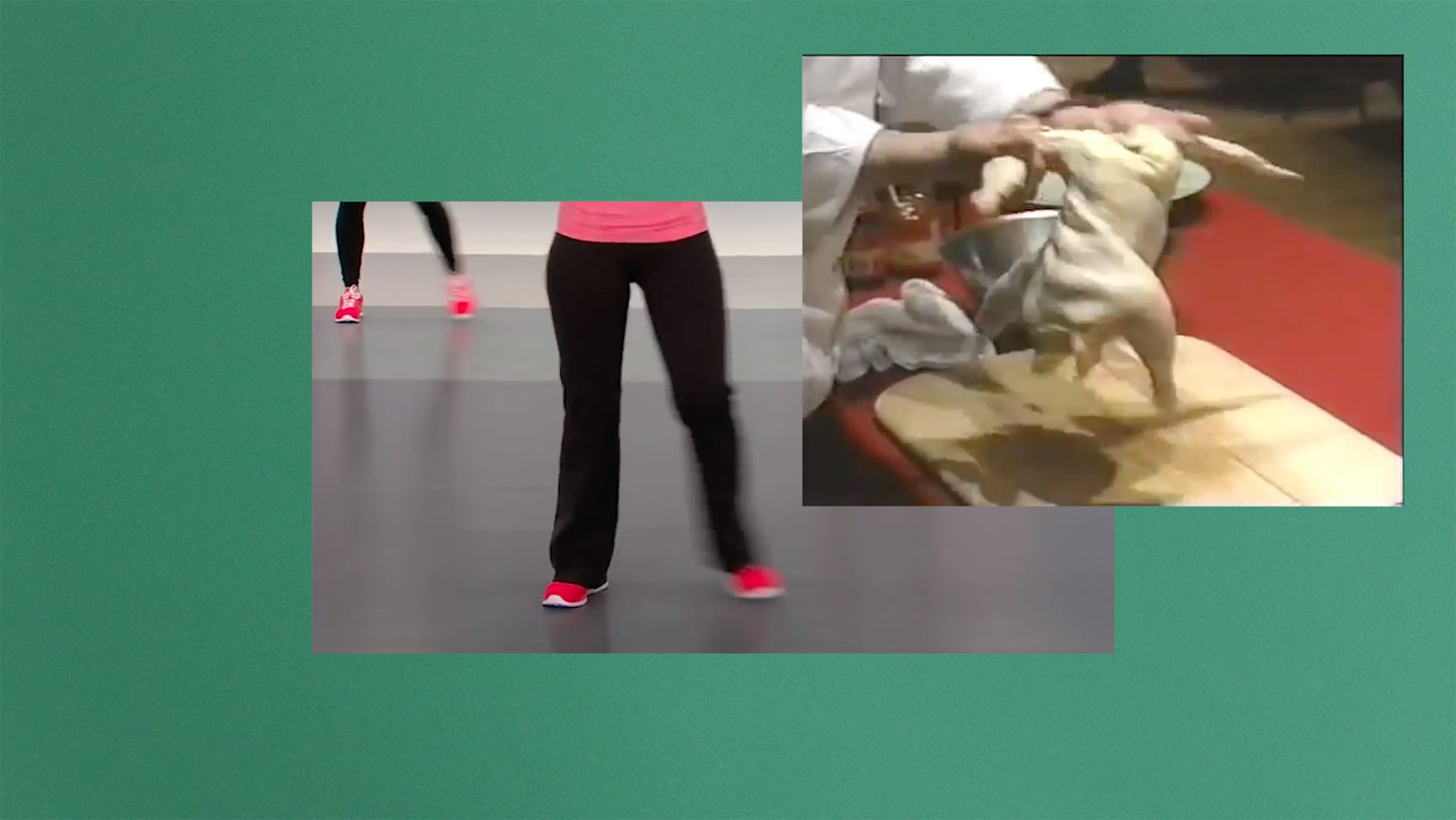

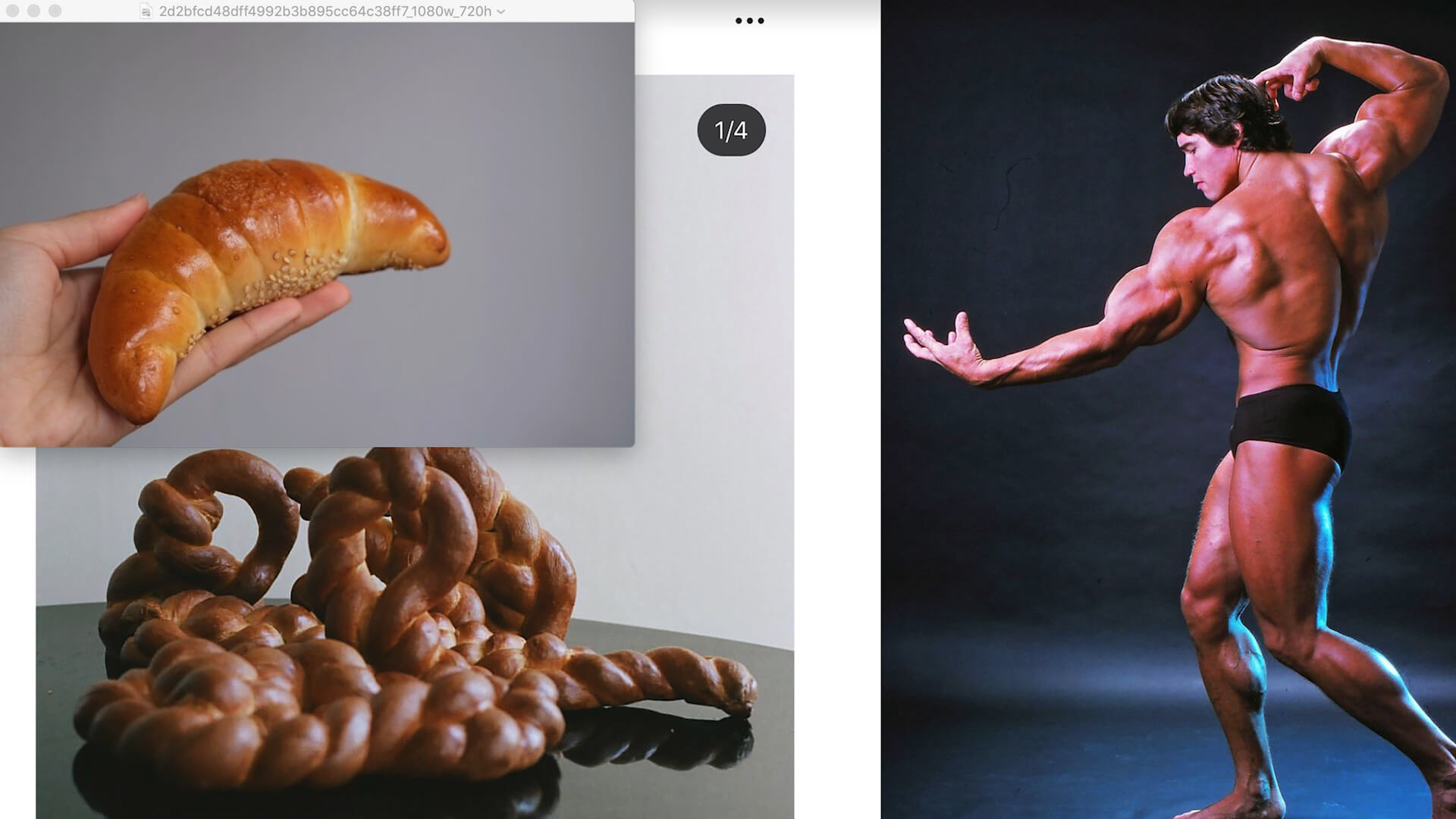

Tang’s aesthetic does not perform exclusively on the visual level. Viewers of Tang’s works might occasionally chuckle at her playful take on the everyday—for instance, her query whether the banknote is red or pink in Pink Mao, or her juxtaposition of her naïve childhood drawings with anime in Pretties! Make Up!, or her playful reflection on post-pandemic everyday life in Exceptional Relaxation (2020). The wit and humor of Tang’s works recall a type of comedy known as Mo Lei Tau 無厘頭, which is associated with Hong Kong’s popular culture and is ubiquitous in film media. In Cantonese, the term Mo Lei Tau means nonsensical, illogical, and incongruous—for example, placing unrelated things in contrast or saying random things. A Western parallel of Mo Lei Tau is Monty Pythonesque humor. In Exceptional Relaxation, Tang’s juxtaposition of images resonates particularly with this type of humor. Various photos of home-baked bread are placed next to Arnold Schwarzenegger’s impeccable body; images of fitness Youtubers are in dialogue with a chef preparing food by massaging a chicken with circular motions. One appreciates the humor behind the surprising and incongruous juxtapositions and simultaneously detects the fluidity and hybridity in Tang’s works.

Tang Han,

Exceptional Relaxation, 2020, single-channel video, color, sound, 4’, still.

Courtesy of the artist.

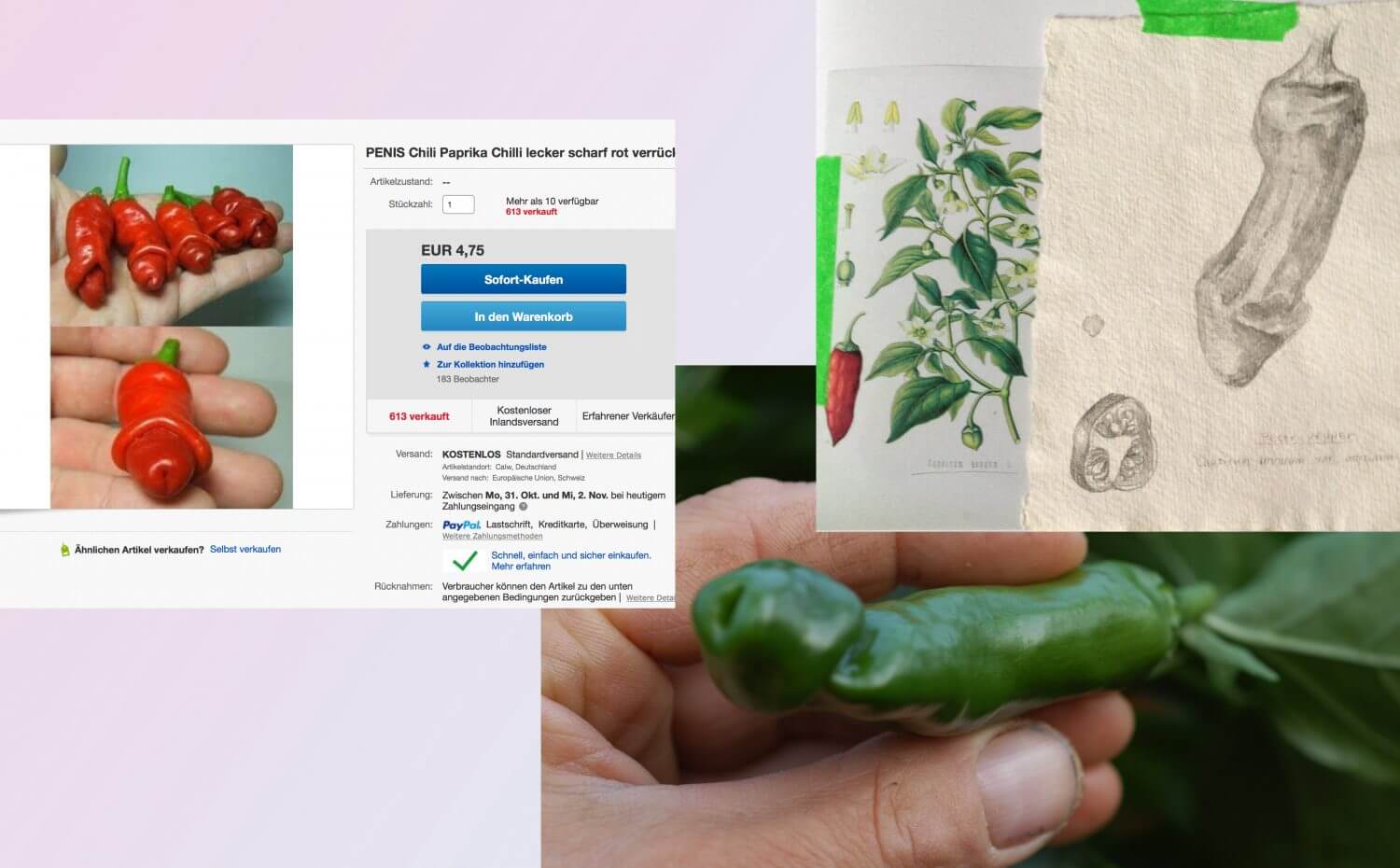

Another aspect of Tang’s approach is her observation of women’s social status. This is reflected in Pretties! Make Up!, in which Tang focuses on how female consciousness emerges by placing her gradually improving childhood drawings and images of Tsukino’s transformation into the soldier Sailor Moon side by side. Her feminist approach can be traced back to her long-term Pepper Project: You’re so Hot! (2015–16). Pepper Project began when Tang accidentally came across a species of pepper on the internet that is known as the peter pepper and is shaped like male genitalia (from which its nickname, the “penis chili,” is derived). Tang purchased seeds and planned to cultivate them herself; simultaneously, she made the decision to tie each plant to a male in real life. She selected twenty-seven random men from different cities in Europe according to her personal preferences. After describing her intentions, Tang asked each man who was willing to be part of the project to choose one of the seedlings that she brought with her and named the selected peppers after their human male counterparts. During the cultivation process, Tang periodically photographed the growth of the plants and sent them to the “chosen men.” In this process, Tang played the role of an inquisitor: whether the peppers were in good shape, large or small in size, healthy or not—all of these criteria seemed to be directly linked to the one male bound to them, and Tang was the one who rendered judgement. In doing so, she wanted to poke fun at the mechanisms of beauty pageants in a patriarchal society and create a way for women to “regain power.”

Tang Han, Pepper Project: You’re So Hot!, 2016, Peter pepper, photography, mixed media. Courtesy of the artist.

Tang has lived in Germany for nine years and says she has expeienced both “positive and negative” discrimination. While Tang’s works to date do not directly address this issue, the Asian diasporic experience is very important to her. There are many reasons why she has chosen to “handle this [topic] with caution,” but none of them are because it is unimportant. Author Cathy Park Hong writes that most white Americans “can only understand racial trauma as a spectacle”; Asian (American) feelings, however, are minor, “the racialized range of emotions that are negative, dysphoric, and therefore untelegenic.”3 Is this the reason that Tang chooses not to directly address Asian diasporic experience in her work? What happens when minor feelings are exaggerated? Is spectacularizing minor feelings the only way to make them visible?

Tang once mentioned that her previous works look for an in-between space of two realities—Germany and China—in everyday life. Being an “in-betweener” herself, she is highly attuned to the complexity of cultures. This might have led her to her approach of keeping distance from both cultures, and it mirrors the Confucian mindset of Zhong Yong 中庸 (doctrine of the mean), which teaches people to be neutral and impartial. The opposite of Zhong Yong is not only to be biased or prejudiced but to be extreme in one’s self-positioning. If the answer to every question could be a yes or a no, both answers represent a certain extremity, that is, they entail focusing on a single possibility and ignoring other equally important possibilities. The neutral, on the other hand, distances itself from each possibility and stands in the middle. It is an attempt to place diversity in a vast network, to give each possibility its own place. Perhaps the mindset of Zhong Yong underlies Tang’s desire to be cautious and exceptionally rational—characteristics that cause Tang’s works to be piled with facts, evidence, and open questions but to refrain from conveying her own biases.

Tang Han (b. 1989) is a Chinese artist based in Berlin and Guangzhou. She studied at the Berlin University of the Arts and Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts. Tang works with a range of media including film, video, installation and painting. Her artistic practice revolves around questions of representation and meaning, which are rooted in her observations of everyday life and social realities. Recent exhibitions and screenings include Kunsthaus Dresden (2021), 38th Kassel Documentary Film and Video Festival (2021), OCAT Shenzhen (2020), How Art Museum, Shanghai (2020), and Bi-City Biennale of UrbanismArchitecture, Shenzhen (2017). Her film PINK MAO, won the Award for Excellence at 34th Image Forum Festival in Tokyo (2020) and the Silver Dove Award in the German Competition at 64th International Leipzig Festival for Documentary and Animated Film in Leipzig (2021). She is currently one of the participants 2021-2022 of the BPA// Berlin program for artists.

Congle Fu received her MA in Global Art History at Freie Universität Berlin. Her research interests include new media art, media studies, and film studies. From a hybrid perspective, she tries to examine modern and contemporary art in Western and Asian cultures. She lives in Berlin.

1 Tang Han, “Tang Han: Everyday Resonance,” Tightbelt, December 2020, 149.

2 Gilles Deleuze, “Postscript on the Societies of Control,” October 59 (Winter 1992): 5.

3 Cathy Park Hong, Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning (New York: One World, 2020): 46–62.